*

LUCIA BEDINI

The ’ideal city’ of Urbino

*

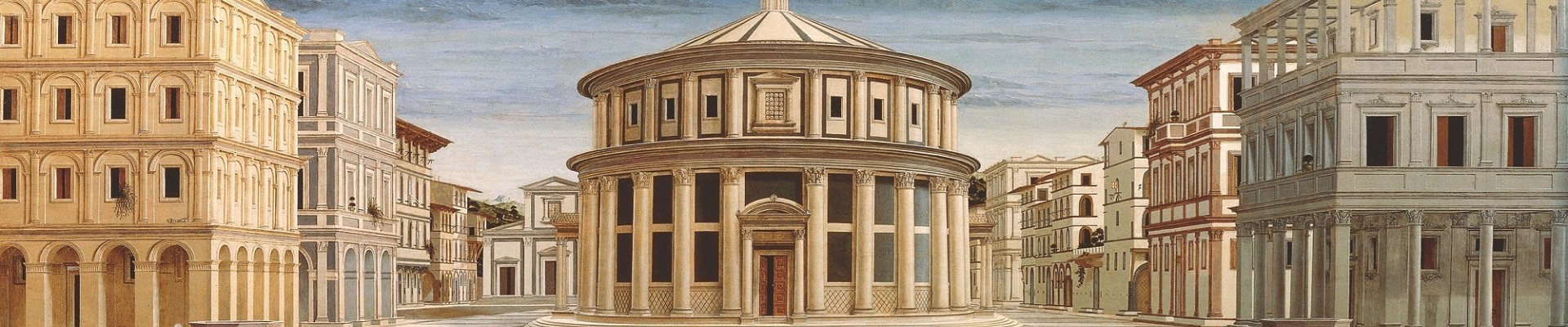

The ’ideal city’ (photo 1) is a painting in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche. It was painted in the second half of the 15th century, possibly commissioned by Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. The theme of the ideal city revived during the Renaissance, when the city once again became the fundamental place for human activity. The first time an ideal city is described in a treatise, it is referred to as ’beauty and order’, and by order is meant measure, proportion, decorum, harmony. In the Middle Ages there were no treatises on the city based on respect for the law and governed by exemplary government. The model of the city was St Augustine’s civitas Dei, which denied the value of earthly residence: ’pilgrim on earth, citizen in heaven’.

The civitas Dei is the heavenly Jerusalem, which is impossible to achieve on earth, because man is stained by original sin, so if the kingdom is not of this world, there is no need to build buildings. In the Middle Ages, the truth of nature was neither logical nor physical, but religious, man was certainly not the ’image of God’, he had been ’made in the likeness of God’. Cities were represented in the circle of walls according to the abstract ideal of the city of God, beauty was linked to God’s creation, not to an aesthetic and rational evaluation of urban spaces; it was a beauty that aroused astonishment and wonder; not a rational, mathematical, scientific beauty, linked to the awareness of the dignity of man as a creator who could build, create under the banner of the geometric organisation of space through perspective. In the 15th century, human culture became the work of man, and man’s dignity lay in his ability to build and create his own physical universe, his own ideal state, without supernatural intervention.

Thus we pass from the city of God to the city of man, destined for a society dictated by rules of harmony - given by a wise and just government - which are reflected in the balance and rationality of architecture and urban spaces. We return to the past to create an ideal continuity in the institutions that contemplated the highest values of freedom, justice, peace, respect and harmony. The architectural structure of the city is thus combined with the political-social structure whose aim is harmony.

The 15th century saw the birth of faith in man and his ability to build. Renaissance space was the result of a reorganisation of the world, a space whose measure was man: "Man is the measure of all things" (Protagoras).

The change in the city was also conditioned by the translations of Plato and Aristotle from Greek into Latin by humanists such as Salutati, Bruni, Decembrio and Acciaiuoli. Acciaiuoli ’while governing, he was philosophising and while philosophising he governed the Republic of Florence’. At first, the humanists donated the translations to the lords, then the contrary happened: Federico da Montefeltro and Cosimo Medici commissioned them. Federico’s request is justified by the desire to learn the political strategy of good government. The prince wants to learn how to be a good administrator - never a master - of the city.

"And perhaps we need to turn to Alberti’s pages in order to rediscover that balance in the work of the prince who intends to reign in his own house and not be a tyrant of peoples; that house, which must be outside and inside, in matter and in spirit, order, rationality, harmony, in order to be the centre where all human beings can come together in a consortium of spirits and intentions" (Brunelli, 1970 ).

Cusin writes that Federico Montefeltro’s political work, even though this may seem a paradox, is the ducal palace in Urbino.

This new prince deals paternally with the people and considers it his duty to guarantee peace among his citizens; he is the son of a particular historical moment, in which we see the transformation of the leader, who has become such by force, into the princeps of the State. The social microcosm, the result of the evolution characteristic of the Italian Commune, accepts the idea of the benevolent prince. The ideal dualism between people and sovereign is now sanctioned by a serene coexistence. For the military man Federico da Montefeltro, the studia humanitatis prevailed over war and led him to choose to fight only when strictly necessary.

Politics became in the Renaissance the highest expression of the power and constructive capacity of the prince. Not war, but peace is his ideal: to preserve rather than to extend the State.

Federico looks for satisfaction in other manifestations than the pure will of power. It is a consequence, but also a great achievement, of the spiritual form of Humanism: the prince of mercenary leaders is ready to choose a form of life where the military function is not placed in the foreground. Vittorino’s pupil prefers the system of armed peace; giving meaning to his work of government prevails over the political problem.

From the practical activity of the political leader, man escapes in search of a higher atmosphere, where he can recreate his spirit, in a beauty of life that aims to perfect the world itself. Hence the constructive work, the spiritual improvement imposed on himself and the surrounding world, as Vittorino da Feltre taught him.

Behind this attempt to achieve a dreamed perfection in reality lies the widespread aspiration of the European educated classes to create for themselves an imaginary perfection as opposed to a coarse reality that they wish to forget. But Federico was no longer satisfied with an ideal that was impossible to realise; here, in the very acts of Federico’s life and in the customs of the Urbino court, we still move towards a dream or a fiction, but with the confidence of building a reality (Cusin, 1970). To work, to give work, to build in one word. The desire for renewal was at the heart of the spirit of the century. This eagerness to build is manifested in the great architectural constructions: to build houses, palaces, rationally, solidly, based on sound and rational criteria of construction technique necessary for works of war and works of peace. And here is the architectural work that symbolises the construction of the State, and here is the careful organisation of the Urbino court, which must be second to none, but which must surpass all of them in terms of order and method, as can be seen in the layout of the rooms in the Ducal Palace. Filarete, in his treatise on architecture, compares the state to a construction in which the prince is the master builder and the engineer who must arrange all its parts.

Leon Battista Alberti too conceived the prince as being at the service of the community, who must preserve the peace and freedom of his citizens in order to lead them to the happiness of the soul.

The re-elaboration of architectural space for Alberti and Brunelleschi must be coordinated through the rules of perspective. Renaissance perspective is the basis for the construction of real space (Urbino and Pienza) and the Urbino panel is an example of the relationship between perspective and town planning, so that the ideal city is the meeting point between political and aesthetic thought. In the painting there is the ideal model of the Renaissance city: harmony of geometry, form and proportion.

The court of Urbino is linked to a vision for which the reality given by divine creation is regulated by mathematical ratios, by numerical proportions that therefore represent the divine measure of visible reality and on which man must base himself in reproducing reality itself, especially architectural space.

The theme of the Renaissance city implies the formal qualification of the urban structure, not only in the role of the city as a place for civil living. Speculation on the city is interwoven with mathematical, philosophical and political themes and becomes central in the transition between the ancient and modern worlds. The relationship between lord and city is symptomatic. With the rise of seigniories and principalities, the city became, with the wealth and quality of its architecture, a fundamental point of political and cultural promotion, the visible demonstration of the power and prestige of the lord.

The "city in the form of a palace" is the highest achievement, the most extraordinary visual symbol not only of Federico’s power, but also of his intellectual character, of his ability to bring the multiple to unity in the sign of mathematical and philosophical speculation. The architects, mathematicians and artists gathered at Federico’s court were carriers of experiences, ideas and proposals of great variety. The result is a unified vision of the built space governed by the golden rules of measurement and proportion - the palace alone is the image of the city.

Augustine’s opposition between urbs and civitas is evident: the urbs is built by men, and therefore can be destroyed; the civitas is based on men, and will exist as long as there are men.

Philosophy and rhetoric enter into the curriculum of young students who are educated in active life, in the formation of a civic sense.

The consideration of mathematics also changes. In the Middle Ages it was studied in the context of metaphysics and theology. Merchants who needed to find solutions to their calculation problems were not interested in such mathematics. Humanistic schools such as that of Vittorino da Feltre have the merit of bringing the study of Euclid into the quadrivium.

The ’ideal city’ is a rational city, scientifically built according to the rules of mathematics, i.e. according to reason. This will lead to Raphael who - the son of Urbino - will operate a synthesis between thought and image. In the ’School of Athens’ the arts of the quadrivium (arithmetic represented by Pythagoras, geometry by Euclid, music by the biblical Tubalcain, astronomy by Ptolemy), the arts preferred by Duke Federico, are in an absolutely privileged position, as if to seal Raphael’s continuous relationship with the culture that came from his Urbino training. The scientific-mathematical approach, which is the basis of the Urbino Renaissance, was clearly absorbed by Raphael during his training in his native city.

In the Urbino painting - proof of the new rational thought - the protagonists are arithmetic and geometry, the liberal arts used to design and create. In the license issued in 1468 by Federico to Luciano Laurana, they are defined as "in primo gradu certitudines".

The theme of the ideal city had already been dealt with by Plato, from a philosophical and political point of view. Plato recognised the architect’s task of giving form to reality (architecture is based on the truth of geometry). Both the city and society are expressed by the politics of the enlightened lord. The form of the city is an expression of the way the state is governed. For Federico, building according to reason is a form of government.

Federico, who received a humanistic education from Vittorino, developed the concept of the ideal city on two levels: theoretical and practical; theoretical linked to the way of conducting the state, practical linked to the realisation of buildings and cities.

Lords were the first patrons of rational cities and a collaboration, an alliance, was born between the prince and the architect.

Federico is the only prince whose assumption of power was sanctioned by a pact with the people and a promise to govern wisely and correctly for the well-being of the citizens. Federico took his commitment seriously and the relationship with the citizens was one of mutual trust; the palace is a testimony, a structure without barriers, open to the urban reality which, with its winged façade, assumes agreement and harmony with the city. The harmony and rationality of form reflects the harmony of social order and good governance. A right and illuminated government creates a peaceful and harmonious society.

Good governance is not only based on evangelical principles, it is necessary. Federico is a vicar; in these centuries in the territory of the church state, some local oligarchies want to be subject directly to the church (without the mediation of a lord) in order to have more power. That is why a careful internal and foreign policy is needed. The internal policy requires a peaceful situation within the state; its visible fortification; the creation of a loyal nobility. Foreign policy requires strong political and military alliances outside the church state.

It is the profession of arms that guarantees both.

Domestic policy is the policy of good governance. It is based on three principles: quick administration of justice, work for all, taxation as light as possible. The programme is supported by a lucid and intelligent awareness that good governance pays in strengthening of power.

Plato in The Republic (IV, 427 et seq.) already points to the virtues, and in particular Justice, as the basis of the perfect city and the moral perfection of the individual (Patrizia Castelli, 2001).

The concept of idea also derives from Plato. For Plato, the idea is the structure, the base; then the idea develops and moves on to the project, and finally to the realisation.

In the 1400s, when man regains his dignity, he becomes artifex, he creates, he conceives, he designs, he realises, and the space for man is a space with a lucid, clear, limpid architecture, created with the tools of the scientist: ruler, square, protractor, compass, numbers, calculation, arithmetic, geometry, the disciplines used to create harmony, measurement, proportion.

This scientific approach can lead us to think that what we see is true; who among us would dare to doubt the truth of science? What we see in the ’ideal city’ can be considered something scientifically true, credible. What do we see in this table? An ideal, that is, an idea, a vision. If it had been commissioned by Federico, we could see his ideal. Federico is a politician, in the etymological sense of the term, with the nomen matching the res. His ideal is the common good, good government, popular consensus.

In the painting we see a city/government founded on beauty, order, harmony, measure, decorum, security, proportion, balance, equality; the buildings are the same height, they are levelled, a probable reference to equality in dignity.

Federico’s philosophical training is evident. The ancient philosophers (Plato, Parmenides, Plotinus) had a monistic view of the universe, not a dualistic one, as is the case today, with the distinction between subject and object. Today, the subject presumptuously believes that it can dominate, control and manage the object; for example, the environment is considered an object. There is no awareness that man and the environment are one, that man without the environment cannot live.

According to the monistic view, the subject and the object are two sides of the same coin, and this leads to an attitude of mutual respect. The other is considered a subject. Anyone who feels himself to be an object of his interlocutor soon realises that the relationship is not meant to last.

Montaigne said it ’limps’ because it is not equal. The other must be a subject in every relationship: between partners, parents and children, teachers and students, doctors and patients, rulers and ruled. Here ruler and ruled are on the same level.

In the medieval city-planning, the tower-house still indicated the importance of the owner. The most powerful man would raise his tower; today he raises his voice, sometimes even his hands. The same idea of equality also applied to justice. J. Sabatino de li Arienti reports that Battista "was merciful, with great zeal for justice... she wanted every man to be equal in justice".

In the centre of the painting is a temple. Plutarch writes that we will never see a city without a temple.

"If you travel the earth, you may find cities without walls, without letters, without kings, without houses, without riches, without coins, without theatres and gymnasiums; but no one has ever seen nor will ever see a city without temples and without gods" (Plutarch, Adversus Colotem, XXXI, 4-5)

The temple is the seat of religion and knowledge.

2,500 years ago, philosophy was born in a temple, where the priest/philosopher was the first to ask those questions about man that man still tries to answer today: who is man? Where does he come from? Where is he going? Homo homini lupus or homo homini deus? There are only a few years’ difference between Plautus and Caecilius Statius. Man is both aggressive and divine. How can this be explained? On what does this difference depend? It depends on the idea, on the vision. On how we see the world. Whether it is a right view (right, just, comes from the latin word ius-iuris) or a hooked, egoistic, egocentric one; whether the other is a hospes or a hostes, a subject or an object, an aim or a means, to use Kantian terms.

The temple could house our ideal, our vision of the world; if religion is at the centre of our vision, the temple could be a baptistery; if man is at the centre, a pantheon; if health, it could be a hospital; if research, it could be a laboratory; if justice, it could be a court of law; if the family, it could be a home; if education, it could be a school... our ideal is the reason of our life, the goal of our existence, our daimon. The oracle of Delphi invited us to know ourselves, to know our passion, our vocation, and to know our limits, to be aware that there is something greater than ourselves, that is not us.

The door of the temple is open. This too can be a message, we can enter the temple that contains our ideal, we can achieve our goal; but it is open, not wide open, we must open it to enter. The road to enter requires commitment, effort, sacrifice, toil; it is the road of the Ancients, of virtus, not the easy one that can be bought with money or corruption. And it is the only road that leads to the conquest of something lasting. Once we have entered the temple and achieved the ideal, nothing and nobody can take it away, not an earthquake, not a financial crisis, not a tyranny. And once the ideal has been achieved by our own efforts, above all, we will be free, and will be able to utter that simple but often impossible syllable, that is: "no". If we are free, if we are not servant, we will afford to say “no”!

Another aspect that is noticeable in the painting is the sense of order, decorum, harmony, balance, proportion in the parts, in the distribution. The buildings are all the same height - equality in dignity - but inside they are all different, like men, we are all different, meaning diversity as a strength.

Even the painting itself could be a union of forces. This could also be the reason why it is not signed. If the painting really represents Federico’s idea, his vision, it is easy to think that it is the result of several voices. After all, at the court there were international excellences of humanistic and scientific knowledge. Urbino was the seat of "mathematical scientific humanism", as A. Chastel defined it. Aware that he could not compete with the philosophical humanism of Padua, the artistic humanism of Florence and other Italian Renaissance centres, Federico affirmed something in Urbino that could not be found in any other court: the science. Scientists, architects, engineers and treatise writers arrived in Urbino (Luciano Laurana, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Leon Battista Alberti, Piero della Francesca, Paolo da Middleburg, Luca Pacioli). It is no surprise that in the ’School of Athens’ Raphael places the arts of the quadrivium in the foreground.

Several artists may have contributed to the design of the panel. If we accept the hypothesis that the painting may represent Federico’s political ideal, we cannot think that a prince could design such a sophisticated ideal on his own. It is easy to assume that he called upon a team of experts: architects, scientists, treatise writers, town planners, jurists, philosophers... The architects included Leon Battista Alberti, who spent every summer at court from 1464. When composing ’De re aedificatoria’, he was inspired by Vitruvius’ treatise ’De re architectura’. The two terms in both languages - Latin and Italian - have the same difference in meaning: to build and to edify. The word “to build” is an architectural term, it means to erect a building; “to edify” has also a pedagogical meaning, it also means to train the prince who will inhabit the building. A magnanimous and liberal prince will live in an open and hospitable palace, while a tyrannical prince will live in an armoured palace. The winged façade of the Ducal Palace of Urbino (photo 2) embraces the visitor, it is welcoming, hospitable, like an open book; the courtyard, the main staircase (photo 3), the large luminous rooms confirm the owner’s hospitality and liberality.

L.B. Alberti in ’De re aedificatoria’ melts geometry with philosophy; science and philosophy help to build. The ideal city is designed by a philosopher and a scientist to educate the prince to rule wisely.

Alberti dedicates pages to the education of the prince and to Plato’s philosophy, according to which a king must be a philosopher because the basis of philosophy - and politics - is ethics, so philosophy and politics are linked by ethics.

The aim of politics is the happiness of all (eudaimonia).

The aim of ethics is to produce a good life for both individuals and the community.

For Plato, it is impossible to build a good community life if the life of individuals is not already good. Politics penetrates the soul as an obligation that no one can escape: the obligation to place irrational impulses under the control of reason, just as philosophers must be placed at the head of society in the state. A just and well-ordered state, where both the individual and the whole are happy, is one where everyone performs the task for which he is predisposed, based solely on natural differences. Plato regarded as negative the irrational passion for material goods, for the private successes of individuals at the expense of what is universal, common, useful to all.

A good state will be achievable if rulers are able to make their own interests match with the common interest.

Plato argues that the philosopher believes firmly in his ideals for which he is prepared to sacrifice his life. In his treatise ’How I see the world’, Einstein wrote: ’A man’s true value is determined by examining to what extent and in what sense he has come to rid himself of the ego’ and place himself at the service of something greater, more important than himself, such as an ideal.

Heroes such as Socrates, Giordano Bruno, the young men of the Second World War, the Italian magistrates Falcone and Borsellino lost their lives for their ideals, for something greater than themselves, such as the Fatherland, the State, the Justice. Even for Aristotle, man comes before the state, but only chronologically (man, family, village, city, state), because rationally the state comes before everything: there is no man more important than the laws of the state. If there is a government where man is more important than the state, that government is called tyranny and is ruled by corruption.

Federico - like Alberti - also melt geometry with philosophy; in his studiolo (photo 4), among the illustrious men, Euclid is portrayed together with Vittorino da Feltre (photo 5). The intention of melting philosophy with geometry is evident in the depiction of Euclid holding a compass in his hand and in the inscription under the portrait ’Euclid of Megara’. Euclid the philosopher is from Megara, while Euclid the scientist is from Thales. Some scholars assume a mistake, a confusion between the two Euclides; it is easier to assume that it is a fusion of roles, rather than confusion. Both Euclid and Vittorino are represented in the double role of scholar and scientist (Vittorino master of the arts of the trivium and the quadrivium; Euclides, philosopher and scientist). Federico had studied the Platonic philosophy at the Casa Gioiosa and he asked Acciaiuoli, an expert Florentine Greek scholar, to translate from Greek into the vernacular the main texts on ethics and politics by Plato and Aristotle. Federico knew that good government was the only way to assert and confirm his power. Federico represents what Machiavelli later called the ’new prince’. He found himself governing this dukedom in accordance with a pact made with the people. As Machiavelli states, the main concern of a new prince is the preservation of the state. Federico is the vicar, therefore precarious, of the pope and depends on him. How can he consolidate his power? With a lucid, intelligent, shrewd, wise policy of good government. This is why he turns to Acciaiuoli.

Federico realised his ideal with the help of his wife, the young Battista Sforza, to whom he dedicated a place of honour in the famous double portrait by Piero della Francesca (photo 6), now in the Uffizi, Gallery in Florence, the first double portrait in the history of Italian art. At a time when the portrait was the artistic genre par excellence, "not to die even after death" (E. Gombrich), Federico commissioned a double portrait, with which he let the world know that without Battista he would never have become Federico da Montefeltro.

Battista grew up at the court of Milan, under the guidance of Bianca Maria Visconti who had organised the school for her and all her husband’s children according not to the gender of the pupils but to their learning ability, so that the best students were taught by the best teachers. Battista had grown up with the conviction that males and females had the same abilities and opportunities; when she arrived in Urbino, she caused ’all Italy to gossip’ about her initiatives, which were considered daring but met with her husband’s approval. Federico, aware of the cultural level, intelligence and sensitivity of his young wife, entrusted her with the role of government; during his many long absences from the dukedom, she was the man of state, defined in many documents as "princeps" and "dux". She made the laws, dealt with justice, promoted the foundation of the college of doctors of law that was to become the first faculty of the University of Urbino (The Law faculty); when there was a crime, the trial was the next day; she made a law according to which trials could last no longer than 15 days so as not to harm the dignity of the citizens that she felt it was her duty to protect. By ’dignity’, Battista means that every citizen of the duchy must have a job, a home and a family. "She is much more than a symbol: she is the "princeps" who manages power with the full awareness that its foundation and its "security" is "in the satisfaction of the people" (M. Bonvini Mazzanti, 2001). This is part of the domestic and foreign policy governed by the profession of arms. Let’s think of the wars, the fortifications of the dukedom, the war industry, armour and weapons, there was work for everyone. Battista set up a "charity spy" in the dukedom (already introduced in Milan by her aunt Bianca Visconti) who received a salary with the task of wandering around the dukedom and investigating - with great discretion - the well-being of the citizens, to check that everyone was well. If someone needed help, Battista would intervene: for an old person to be cared for, a sick person to be cured, a girl of marriageable age without a dowry, for someone who lost a job, a family member, a house, etc. She wanted to know everything. She wanted to be aware of critical situations so that she could intervene to resolve them. She was convinced that everyone must have a healthy life, aware that a society is healthy when everyone is healthy.

In this period, the importance of the harmonious relationship between the particular and the universal, the microcosm and the macrocosm, was revived; Vitruvius’ man - which would be taken up by Leonardo - represents the harmony of the parts with each other and with the whole: just as a heart without the other organs has no value, so who will rule without the people? When Federico heard that a craftsman had incurred a debt and was in danger of closing his workshop, he went to the shop to ask what the craftsman was doing. He was delighted with the quality of the craftsman’s work and asked to enter into partnership with him by handing over a sum of money. The craftsman thus repaid the debt, happy to have received the prince’s approval, he did not feel the mortification of having received alms! This is what people expect from rulers.

Battista invests a lot of money in culture, aware that the source of all evil is ignorance. "The educated man is more of a man; the uneducated man is similar to and worse than the animal; just as nature made fish fit to swim and birds fit to fly, so it made men fit to learn: ignorance is the cause of all evil; the only way to improve the world is culture" (M. Bonvini Mazzanti, 1993). Battista carried out an incomparable literacy operation: " it is better to have a fat and cultured people than a thin and ignorant one".

In Urbino, politics is part of culture, not the other way around. Battista considered politics to be one of the three handmaidens of moral philosophy, since the task of politics ’is to teach the things that concern the city and how each person should take care of the state so that he can live in it peacefully and receive honour and esteem’. Battista states that she owes much to rhetoric because "it teaches me a sure way to pursue the education of the mind, so as to make me capable of speaking with wisdom, but also with doctrine, propriety and elegance... with it we can obtain the profit of ourselves, of parents, of family, of friends, of all fellow citizens" because the orator has the power to persuade what he wants, "but he must not want except what is right and just". So for Battista, rhetoric is at the service of politics. Cicero is the author most read and loved by the princess. In the "Jocundissimae", Battista strongly defends philosophy. Those who do not devote themselves to philosophy “remain inexperienced in civil laws... and human customs, of which one must have more experience than of anything else”. Philosophy is a useful guide in worldly matters and in the conduct of the state. Moreover, for Battista, the greatest love of all is love of country, because ’it is an affection, an extraordinary charity innate in our minds, stronger than love of children, attachment to family and relatives, devotion to parents, and there is no more honourable feeling for man than this’.

The painting of the ’ideal city’ can be considered a declaration of the ideals of the two princes, sometimes called ’twins’, who share the ideal of good government. They are partners and collaborators. Federico earns a lot of money, and with the help of his wife, he invests it in initiatives in favour of the citizens. Federico earned a lot of money because he offered two guarantees: military success (he had specialised corps trained and prepared) and loyalty: the word is sacred, "money has no value except to be spent" and for something of no value the duke never lost his dignity and professionalism; he never sold his soul for money, also because if you sell your soul for money, what will you buy it back with? The commissioner who engages Federico is sure to spend his money well. The duke’s army also worked in peacetime under the guidance of military architects and carried out works such as fortifications, roads, aqueducts and palaces. The money earned from the military campaigns was then used for the common good.

The panel should be read alongside the continuous references to ideal cities inlaid in the five doors of the palace (photo 7), a mirror and model of a perfect ideal state. These doors are in the duke’s private appartment, not accessible to everyone, and represent the old and the new, the ancient and the modern, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the castle and the palace, as if Federico was thinking, elaborating, conceiving, designing an ideal city made up of old and new, past and present, aware that there is no future without the past. In order to move forward, it is always necessary to preserve something from the past, what Hegel then called Aufhebung, "preserving by overcoming" or "overcoming by preserving". Federico starts from the past and the present and arrives at the future, at the ideal city. In the angels’ room, in the public area of the palace, in an inlaid door is his ideal city, with harmonious structures, with reference to decorum, harmony, order, measure, proportion, technically perfect.

Inlaid in the upper panels, Apollo and Minerva (photo 8), the two divinities in charge of guarding the ideal city, represent harmony and wisdom, without which an ideal cannot be achieved (at home, in the office, at school, in parliament). In the same room, to enter the audience room, another door is a visiting card, with arms and arts; we enter aware that we are being received by a man of arms and culture, balanced between active and contemplative life. In the door between the Angels’ room and the bedroom, on the other hand, are inlaid Hercules and Mars (photo 9), the divinities of virtue and war, a reference to Federico’s pax armata. Cusin writes: "Urbino, the new Rome, can be defined as the illusion of politics. A reality that precedes utopia, as a political aspiration of the modern world" (F. Cusin, 1970).

*

Your comments

-

Beautiful article ! Thanks, Mauro

05/06/2020 -

Submit your comment

This blog encourages comments, and if you have thoughts or questions about any of the posts here, I hope you will add your comments.

In order to prevent spam and inappropriate content, all comments are moderated by the blog Administrator.

Access your Dashboard

Did you forget your password?

Did you forget your password? Ask for it! Click here

Create an account

Not yet registered? Sign up now! Click here